Lion Loose Again Other Lion Mane Fallls Out

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/two-male-lions-Kenya-631.jpg)

Craig Packer was behind the wheel when we came across the massive cat slumped in the shade below a spiny tree. Information technology was a dark-maned male, elaborately sprawled, equally if it had fallen from a slap-up top. Its sides heaved with shallow pants. Packer, a Academy of Minnesota ecologist and the globe's leading lion expert, spun the wheel of the Country Rover and drove directly toward the creature. He pointed out the lion's scraped elbow and a nasty puncture wound on its side. Its mane was full of leaves. From a altitude it looked like a deposed lord, grand and pitiable.

Since arriving in Tanzania's Serengeti National Park but that morning, I'd gaped at wildebeests on parade, droning baboons, gazelles rocketing by, oxpecker birds hitching rides atop Cape buffaloes, hippos with bubblegum-colored underbellies. The Serengeti commonly dazzles outset-time visitors, Packer had warned, making us lightheaded with an abundance of idyllic wildlife straight out of a Disney song-and-dance number.

The sublime brute just 15 feet away was my outset wild Lion. Male person African lions tin can be ten feet long and weigh 400 pounds or more than, and this 1 appeared to exist pushing the limits of its species. I was glad to be inside a truck.

Packer, though, opened the door and hopped out. He snatched a stone and tossed information technology in the big male'south direction.

The lion raised its head. Its handsome face was raked with claw marks.

Packer threw another stone. Unimpressed, the king of beasts briefly turned its back, showing hindquarters every bit shine as cast bronze. The creature yawned and, nestling its tremendous caput on its paws, shifted its gaze to us for the first time. Its eyes were yellow and cold like new doubloons.

This was one of The Killers.

Packer, 59, is tall, skinny and sharply angular, like a Serengeti thorn tree. He has spent a adept chunk of his life at the park's Lion Business firm, a physical, fortress-like structure that includes an office, kitchen and 3 bedrooms. It is furnished with a faux leopard-skin burrow and supplied simply sporadically with electricity (the researchers turn it off during the twenty-four hours to salvage energy) and fresh water (elephants dug upwards the pipelines years ago). Packer has been running the Serengeti Lion Project for 31 of its 43 years. It is the most extensive carnivore report always conducted.

He has persisted through cholera outbreaks, bouts of malaria and a 1994 canine distemper epidemic that killed off a tertiary of the 300 lions he'd been following. He has nerveless king of beasts claret, milk, feces and semen. He has honed his distressed wildebeest calf call to get his subjects' attention. He has learned to lob a defrosted ox eye total of medicine toward a hungry panthera leo for a study of abdominal parasites. And he has braved the colorlessness of studying a brute that slumbers roughly 20 hours a day and has a confront equally inscrutable equally a sphinx'southward.

Packer's reward has been an ballsy kind of science, a detailed chronicle of the lives and doings of generations of prides: the Plains Pride, the Lost Girls ii, the Transect Truants. Over the decades in that location have been plagues, births, invasions, feuds and dynasties. When the lions went to war, equally they are inclined to do, he was their Homer.

"The calibration of the lion study and Craig Packer's vigor equally a scientist are pretty unparalleled," says Laurence Frank, of the University of California at Berkeley, who studies African lions and hyenas.

Ane of Packer'due south more than sensational experiments took aim at a longstanding mystery. A male person lion is the only cat with a mane; some scientists believed its role was to protect an animal'south neck during fights. But because lions are the only social felines, Packer thought manes were more probable a message or a condition symbol. He asked a Dutch toy company to craft four costly, life-size lions with low-cal and dark manes of different lengths. He named them Lothario, Fabio, Romeo and Julio (as in Iglesias—this was the late 1990s). He attracted lions to the dolls using calls of scavenging hyenas. When they encountered the dummies, female lions almost invariably attempted to seduce the nighttime-maned ones, while males avoided them, preferring to attack the blonds, peculiarly those with shorter manes. (Stuffing all the same protrudes from the haunches of Fabio, a focal bespeak of Lion Business firm décor.)

Consulting their field data, Packer and his colleagues noticed that many males with brusque manes had suffered from injury or sickness. Past contrast, dark-maned males tended to be older than the others, have higher testosterone levels, heal well afterwards wounding and sire more surviving cubs—all of which fabricated them more desirable mates and formidable foes. A mane, it seems, signals vital information well-nigh a male'south fighting power and health to mates and rivals. Newspapers across the globe picked up the finding. "Manely, lady lions look for night colour," 1 headline said. "Blonds have less fun in the panthera leo world," read some other.

Lately, Packer'due south research has taken on a new dimension. Long a dispassionate student of lion behavior and biological science, he has become a champion for the species' survival. In Tanzania, dwelling house to as many equally half of all the wild lions on earth, the population is in free fall, having dropped by half since the mid-1990s, to fewer than 10,000. Across Africa, up to one-quarter of the world's wild lions have vanished in little more than than a decade.

The reason for the decline of the rex of beasts can exist summed up in one word: people. As more Tanzanians accept upwards farming and ranching, they push farther into king of beasts state. Now then a lion kills a person or livestock; villagers—who in one case shot simply nuisance lions—have started using poisons to wipe out whole prides. Information technology is not a new problem, this interspecies competition for an increasingly deficient resource, only neither is it a elementary 1. Among other things, Packer and his students are studying how Tanzanians can alter their creature husbandry and farming practices to ward off ravenous felines.

Scientists used to believe that prides—groups of a few to more than a dozen related females typically guarded past 2 or more males—were organized for hunting. Other aspects of the communal lifestyle—the animals' affinity for napping in giant piles and even nursing each others' young—were idealized as poignant examples of animal-kingdom altruism. But Packer and his collaborators have institute that a pride isn't formed primarily for catching dinner or sharing parenting chores or cuddling. The lions' natural earth—their beliefs, their complex communities, their evolution—is shaped by one brutal, overarching force, what Packer calls "the dreadful enemy."

Other lions.

The Jua Kali pride lives far out on the Serengeti plains, where the country is the dull color of burlap, and termite mounds rise similar small volcanoes. It'south marginal habitat at best, without much shade or cover of whatsoever kind. (Jua kali is Swahili for "vehement dominicus.") Water holes wait more similar wallows, prey is scarce and, especially in the dry out flavor, life is non easy for the pride's iv females and two resident males, Hildur and C-Boy.

Early one morning last August, Serengeti Lion Project researchers found Hildur, a Herculean male with a blond mane, limping effectually virtually a grassy ditch. He was sticking close to 1 of the pride's iv females, whose newborn cubs were subconscious in a nearby stand of reeds. He was roaring softly, maybe in an effort to contact his darker-maned co-leader. But C-Male child, the researchers saw, had been cornered on the crest of a nearby loma past a fearsome trio of snarling males whom Packer and colleagues call The Killers.

The whole scene looked like a "takeover," a brief, devastating clash in which a coalition of males tries to seize control of a pride. Resident males may exist mortally wounded in the fighting. If the invaders are victorious, they kill all the young cubs to bring the pride's females into heat over again. Females sometimes dice fighting to defend their cubs.

The researchers suspected that The Killers, who normally live near a river 12 miles away, had already dispatched two females from a different pride—thus The Killers earned their names.

C-Boy, surrounded, gave a strangled growl. The Killers fell on him, start two, then all 3, slashing and bitter as he swerved, their blows falling on his vulnerable hindquarters. The violence lasted less than a minute, merely C-Boy'south flanks looked as if they'd been flayed with whips. Apparently satisfied their opponent was crippled, The Killers turned and trotted off toward the marsh, virtually in lock step, as Hildur's female person companion crept toward a stand of reeds.

None of the Jua Kali lions had been spotted since the fight, but nosotros kept riding out to their territory to wait for them. We didn't know if C-Male child had survived or if the cubs had made it. Finally, one afternoon nosotros plant JKM, the mother of the Jua Kali litter, lolling atop a termite mound as large and intricate equally a pipage organ.

"Hey in that location, sweetness," Packer said to her as we pulled upward. "Where are your cubs?"

JKM had her eye on a kongoni antelope a few miles away; unfortunately, it was watching her, too. She was also scanning the heaven for vultures, perchance in the hopes of scavenging a hyena kill. She stood upward and ambled off into the hip-loftier grass. Nosotros could run across dark circles around her nipples: she was still lactating. Against the odds, her cubs seemed to have survived.

Mayhap the apparent good fortune of the Jua Kali cubs was linked to some other recent sighting, Packer speculated: a female from another nearby grouping, the Mukoma Loma pride, had been seen moving her own tiny bobble-headed cubs. The cubs were panting and mewling pitifully, clearly in distress; normally cubs stay in their den during the heat of the day. The Killers might have forsaken the Jua Kali females to accept over the Mukoma Hill pride, which inhabits richer territory most river confluences to the north. The woodlands there, said Packer, were controlled by a series of "dinky little pairs of males": elderly Swain and Jell-O; Porkie and Pie; and Wallace, the Mukoma Loma leader, whose partner, William, had recently died.

Packer recalled a like blueprint of invasion in the early 1980s past the Seven Samurai, a coalition of males, several with spectacular black manes, who had once brought down 2 adult, 1,000-pound Greatcoat buffaloes and a calf in a unmarried 24-hour interval. After storming the n they'd sired hundreds of cubs and ruled the savanna for a dozen years.

It took a while for Packer to tune into such dramas. When he first visited the Serengeti lions in 1974, he ended that "lions were actually boring." The laziest of all the cats, they were usually complanate in a stupor, as if they had just run a marathon, when in reality they hadn't moved a muscle in 12 hours. Packer had been working under Jane Goodall in Tanzania's Gombe Stream National Park, observing baboons. He slept in a metal construction called The Muzzle to be closer to the animals. In 1978, when Packer'due south program to report Japanese monkeys savage through, he and a swain primatologist, Anne Pusey, to whom he was married at the fourth dimension, volunteered to accept over the Lion Project, begun 12 years earlier by the American naturalist George Schaller.

By the fourth dimension Packer and Pusey installed themselves in the King of beasts House, scientists were well aware that lions are ambush predators with lilliputian stamina and that they gorge at a kill, each i downing up to 70 pounds in a sitting. (Lions eat, in addition to antelope and wildebeest, crocodiles, pythons, fur seals, baboons, hippopotamuses, porcupines and ostrich eggs.) Lion territories are quite large—15 square miles on the low stop, ranging upwards to nearly 400—and are passed downward through generations of females. Lions are vigorous when it comes to reproduction; Schaller observed one male mate 157 times in 55 hours.

Packer and Pusey set out non just to document lion behavior but to explain how information technology had evolved. "What we wanted to do was effigy out why they did some of these things," Packer says. "Why did they heighten their cubs together? Did they actually chase cooperatively?"

They kept tabs on ii dozen prides in minute detail, photographing each animal and naming new cubs. They noted where the lions congregated, who was eating how much of what, who had mated, who was wounded, who survived and who died. They described interactions at kills. It was deadening going, even subsequently they put radio collars on several lions in 1984. Packer was always more than troubled by the lions' sloth than their slavering jaws. Following prides at dark—the animals are largely nocturnal—he sometimes thought he would go mad. "I read Tolstoy, I read Proust," he says. "All the Russians." Packer and Pusey wrote in 1 article that "to the listing of inert noble gases, including krypton, argon and neon, nosotros would add lion."

Still, they began to see how prides functioned. Members of a big pride didn't get any more to eat than a lone hunter, generally considering a alone animal got the proverbial lion's share. Yet lions ring together without fail to confront and sometimes kill intruders. Larger groups thus monopolize the premier savanna existent estate—unremarkably effectually the confluence of rivers, where casualty animals come to drink—while smaller prides are pushed to the margins.

Even the crèche, or communal nursery that is the social cadre of every pride, is shaped by violence, Packer says. He and Pusey realized this after scrutinizing groups of nursing mothers for endless hours. A lactating female nursed another's young rarely, normally after an unrelated cub sneaked onto her nipple. An alert lioness reserves her milk for her own offspring. In contrast to the widespread belief that crèches were maternal utopias, Packer and Pusey found that nursing mothers stick together chiefly for defence. During takeovers by outside males, solitary females lost litter after litter, while cooperating lionesses stood a ameliorate chance of protecting their cubs and fending off males, which can outweigh females past as much as 50 pct.

Surviving cubs go on to perpetuate the bloody cycle. Juvenile females often bring together forces with their mother'south pride to defend the home turf. Males reared together typically form a coalition effectually age 2 or 3 and set out to conquer prides of their own. (Hard-living males rarely alive by historic period 12; females can achieve their tardily teens.) A lone male without a brother or cousin will oftentimes team up with another singleton; if he doesn't, he is doomed to an isolated life. A group of lions will count its neighbors' roars at dark to estimate their numbers and determine if the time is correct for an attack. The key insight of Packer's career is this: lions evolved to dominate the savanna, not to share it.

As we crossed the plains one morning, the Land Rover—broken speedometer, no seat belts, cracked side mirrors, a burn down extinguisher and a gyre of toilet paper on the dashboard—creaked like an aged vessel in loftier seas. We plowed through oceans of grasses, mostly brown but besides mint greenish, salmon pink and, in the altitude, lavender; the lions we hunted were a liquid flicker, a electric current within a current. The landscape on this day did non wait inviting. Sections of the giant sky were shaded with pelting. Zebra jaws and picked-make clean impala skulls littered the footing. Basic don't concluding long here, though; hyenas eat them.

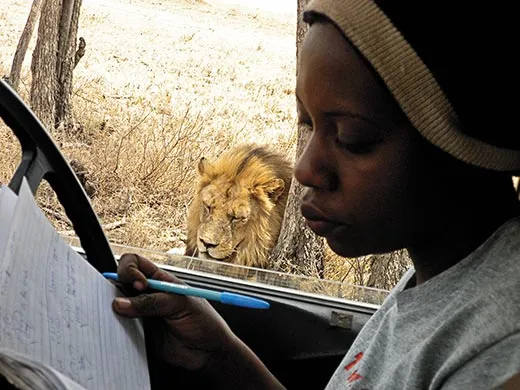

Packer and a enquiry assistant, Ingela Jansson, were listening through headphones for the ping-ping-ping radio bespeak of collared lions. Jansson, driving, spotted a pride on the other side of a dry gully: six or vii lions sitting slack-jawed in the shade. Neither she nor Packer recognized them. Jansson had a feeling they might be a new grouping. "They may never accept seen a machine before," she whispered.

The sides of the ditch looked unpromising, simply Packer and Jansson couldn't resist. Jansson plant what seemed to be a decent crossing spot, by Serengeti standards, and angled the truck down. We roared beyond the bed and began churning upwardly the other side. Packer, who is originally from Texas, let out a whoop of triumph just before we lurched to a halt and began to slide helplessly backward.

We came to residuum at the bottom, snarled in reeds, with only three wheels on the footing, wedged betwixt the riverbanks as tightly as a filling in a dental cavity. The ditch was 15 feet deep, so nosotros could no longer see the pride, but equally nosotros'd slipped downward, a row of black-tipped ears had cocked inquisitively in our direction.

Jansson stepped out of the truck, long blond ponytail whipping around, dug at the wheels with a shovel and spade, and and so hacked down reeds with a panga, or straight-blade machete. Earlier I had asked what kind of anti-panthera leo gear the researchers carried. "An umbrella," Jansson said. Obviously, lions don't like umbrellas, especially if they're painted with large pairs of eyes.

Packer is not agape of lions, specially Serengeti lions, which he says have few encounters with people or livestock and have plenty of other things to eat. To figure out if a sedated lion is truly down for the count, he'll get out of the truck to tickle its ear. He says he once ditched a mired Land Rover within ten feet of a large pride and marched in the opposite direction, his 3-twelvemonth-old girl on his shoulders, singing nursery schoolhouse songs all the fashion dorsum to the Lion House. (His daughter, Catherine, 25, is a student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Wellness. Packer never tried such a stunt with son Jonathan, now 22, although Jonathan was once bitten past a baboon. Packer and Pusey divorced in 1997; she returned to studying chimpanzees.)

Not being handy with a panga, I was sent a brusk distance down the riverbed to gather stones to wedge nether the wheels. Packer's nonchalance was not contagious. I could not decide whether I should creep or dart. Every time I glanced at the grassy riverbanks above I was sure that I would find myself the object of some blond monster's greedy regard. Every bit I bent to hook stones out of the basis, I knew all of a sudden, with complete, visceral certainty, why Tanzanian villagers might rather exist rid of these animals.

I'd already taken stock of their carving-knife incisors and Cleopatra eyes, observed their low, rolling, hoodlum swaggers, heard their idling growls and nocturnal bellows. If you alive in a mud hut protected by a brier fence, if your cows are your banking concern account and your 7-year-quondam son is a shepherd who sleeps in the paddock with his goats, wouldn't you want to eliminate every last lion on world?

"People detest lions," Packer had told me. "The people who live with them, anyway."

Later more than an hour of reed-whacking, rock-wedging and wrestling with mud ladders placed under the tires to provide traction, the vehicle finally surged onto the far side of the ditch. Incredibly, the lions remained precisely where nosotros'd seen them concluding: sitting with Zen-like equanimity on their little doily of shade.

Jansson looked through binoculars, taking note of their whisker patterns and a discolored iris hither and a missing tooth there. She determined this was the seldom-seen Turner Springs pride. Some of the sun-dazed lions had bloodstains on their milky chins. Though they hadn't displayed the slightest interest in us, I uttered a silent prayer to get home.

"Let's get closer," Packer said.

The first true lion probably padded over the world about 600,000 years ago, and its descendants eventually ruled a greater range than any other wild land mammal. They penetrated all of Africa, except for the deepest rain forests of the Congo Basin and driest parts of the Sahara, and every continent salvage Australia and Antarctica. In that location were lions in Uk, Russia and Peru; they were plentiful in Alaska and the habitat known today as downtown Los Angeles.

In the Grotte Chauvet, the cave in France whose 32,000-year-old paintings are considered among the oldest art in the world, there are more 70 renderings of lions. Sketched in charcoal and ocher, these European cavern lions—maneless and, according to fossil evidence, 25 percent bigger than African lions—prance aslope other at present-extinct creatures: mammoths, Irish elk, woolly rhino. Some lions, drawn in the deepest function of the cave, are oddly colored and abstract, with hooves instead of paws; archaeologists believe these may exist shamans.

The French authorities invited Packer to tour the cave in 1999. "Information technology was 1 of the well-nigh profound experiences of my life," Packer says. Merely the dream-like quality of the images wasn't what excited him; it was their zoological accuracy. By the low-cal of a miner'south lamp, he discerned pairs, lions moving in large groups and even submissive behavior, depicted down to the tilt of the subordinate's ears. The creative person, Packer says, "doesn't exaggerate their teeth, he doesn't make them seem more formidable than I would. This was somebody who was viewing them in a very cool and discrete way. This was somebody who was studying lions."

The lions' decline began nigh 12,000 years agone. Prehistoric homo beings, with their improving hunting technologies, probably competed with lions for prey, and king of beasts subspecies in Europe and the Americas went extinct. Other subspecies were common in India and Africa until the 1800s, when European colonists began killing lions on safaris and clearing the land. In 1920, a hunter shot the final known member of the North African subspecies in Morocco. Today, the but wild lions outside Africa belong to a small group of fewer than 400 Asiatic lions in the Gir Forest of India.

Lions persist in a scattering of countries across southeastern Africa, including Botswana, Due south Africa and Kenya, only Tanzania's population is by far the largest. Though devastatingly poor, the nation is a reasonably stable commonwealth with huge tracts of protected land.

Serengeti National Park—at 5,700 square miles, about the size of Connecticut—is perhaps the world's greatest lion sanctuary, with some iii,000 lions. In Packer's study surface area, comprising the territories of 23 prides about the park'south center, the number of lions is stable or even ascension. But the Serengeti is the exception.

Part of the blame for Tanzania's crashing panthera leo population belongs to the trophy-hunting industry: the government allows the harvest of some 240 wild lions a twelvemonth from game reserves and other unprotected areas, the highest accept in Africa. Safaris charge a trophy fee of as little equally $6,000 for a lion; animals are shot while feasting on baits, and many of the coveted "trophy males" have peach fuzz manes and haven't fifty-fifty left their mother's pride yet. The employ of lion parts in folk medicines is another concern; as wild tigers disappear from Asia, scientists have noticed increasing demand for leonine substitutes.

The central issue, though, is the growing human population. Tanzania has three times as many residents now—some 42 one thousand thousand—equally when Packer began working there. The country has lost more than than 37 percent of its woodlands since 1990. Disease has spread from village animals to the lions' prey animals, and, in the instance of the 1994 distemper outbreak that started in domestic dogs, to the lions themselves. The lions' prey animals are likewise popular in the burgeoning—and illicit—market for bush meat.

And so there is the understandable sick will that people acquit lions, which loiter on front end porches, bust through thatched roofs, snatch cattle, rip children from their mother's artillery, haul the elderly out of bed and seize women on the way to latrines. In the 1990s, every bit Tanzanians plowed big swaths of king of beasts territory into fields, lion attacks on people and livestock rose dramatically.

Bernard Kissui, a Tanzanian lion scientist with the African Wild fauna Foundation and one of Packer's former graduate students, met Packer and me in Manyara, a bustling district southeast of Serengeti National Park. Kissui said five lions nearby had recently died afterwards eating a giraffe carcass laced with tick poison.

"Is that one of your written report prides?" Packer asked.

"I'grand suspecting so," said Kissui, who works in the nearby Tangire National Park. He wasn't sure who had poisoned the lions or what had provoked the killings. A month before, lions had killed three boys, ages 4, 10 and 14, herding livestock, only that was in a village 40 miles away.

"Africa is not Africa without lions," Kissui told me, but "human needs precede the wild fauna's. As the number of people increases, we take the country that would have been available to the wildlife and apply it for ourselves. Africa has one billion people now. Call back most what that one billion implies in terms of the time to come of lions. We are heading into a very complicated earth."

Young men from pastoral tribes no longer care to tend cattle, Kissui says. "They want to go to Arusha and drive a auto." So their little brothers are sent into the bush-league instead. Packer and his students have shown that lions tend to target livestock tended past boys during the dry out season.

Packer, Kissui and other scientists are experimenting with ways to go on people and lions safe. Special funds repay herders for lost livestock—if no panthera leo is harmed. They accept suggested that corn farmers in southern Tanzania hang chili peppers in their fields, which repel the bush-league pigs that lions savor, or dig ditches around their crops to keep the pigs out. And Packer is profitable Kissui with a plan that subsidizes herdsmen who desire to supersede their bramble-enclosed paddocks with fences of metal and wood.

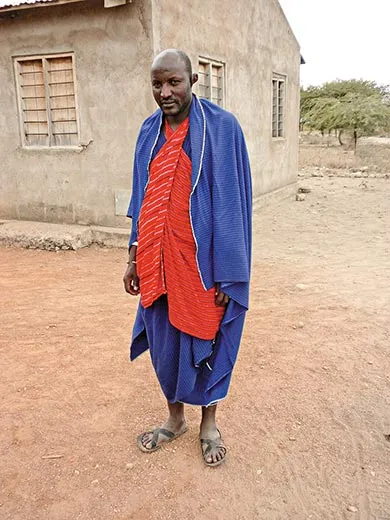

In Manyara we visited Sairey LoBoye, a report participant. He was attired in stunning blue blankets and talking on his cellphone. LoBoye is a member of the Maasai tribe, whose traditional culture centers on safeguarding cattle: teenagers spear lions equally a rite of passage. LoBoye said he simply wanted lions to leave him alone. 2 years ago lions devoured one of his precious bulls, but since installing a modernistic argue, he hasn't had whatever problems and his cattle and children are safer. "Now I can sleep at night," he said.

Packer argues that the Serengeti, like some Southward African parks, should be surrounded by an electric, elephant-proof, heavily patrolled fence that would encompass the whole wildebeest migration route and keep the lions in and the poachers out. The idea has little support, in part because of the tens of millions of dollars it would toll to erect the bulwark.

Packer and Susan James, a former business executive he married in 1999, founded a nonprofit system, Savannas Forever, which is based in Arusha and monitors the quality of rural village life. They've hired Tanzanians to mensurate how evolution help affects such variables as children's height and weight; they'll spread the word well-nigh which approaches are most effective so other programs can replicate them. The hope is that improving the standard of living will bolster local conservation efforts and give lions a ameliorate shot at survival.

As hard as it is for Packer to imagine the prides he has followed for so long ending in oblivion in the next few decades, he says that's the almost likely outcome: "Why am I doing this? I feel like I owe this state something. So 100 years from now there will however be lions in Tanzania."

Before I left the Serengeti, Packer took me to run into a fig tree that had served for decades every bit a lion scratching mail service. Every bit nosotros collection across the savanna, graduate student Alexandra Swanson fiddled with a radio scanner, searching for signals from radio-collared lions, merely we heard only static.

The tree was on a kopje, one of the isolated piles of rocks in the grasslands that are popular lion haunts. Packer wanted to climb upward for a better expect. Lulled, perhaps, by the silence on the scanner, I agreed to back-trail him.

We'd climbed nigh of the fashion up the pile when Packer snapped his fingers and motioned for me to crouch downward. The world seemed to zoom in and out, as if I was looking through a camera'south telephoto lens, and I imagined hot lion jiff on my neck.

Packer, at the peak of the kopje, was waving me closer.

"Do you lot come across that panthera leo?" he whispered. "No," I whispered dorsum.

He pointed at a shadowy fissure beneath the fig tree, nearly 20 feet abroad. "You lot don't see that lion?"

"There is no lion," I said, equally if my words could get in so.

Then I saw i tiny, yellow, heart-shaped face, and so another, bright as dandelions against the grayness rocks. Aureate eyes blinked at the states.

Mothers frequently exit their cubs for long stretches to hunt, but this was simply the second fourth dimension in Packer's long career he'd found an unattended den. Young cubs are near completely helpless and tin starve or be eaten by hyenas if left alone too long. One of the cubs was clearly horrified past our presence and shrank behind its braver sibling, which arranged itself in a princely fashion on the rocks to bask these strange, spindly, cringing creatures. The other cub seemed to forget its fear and bit the bold ane's ear. They were perfect fleecy things. Their coats had a faint tiled pattern that would fade away with fourth dimension.

That dark we camped abreast the kopje, Swanson and I in the bed of the State Rover and Packer in a flimsy tent. Information technology wasn't the most restful evening of my life: in the lion'southward last bang-up stronghold, nosotros were exterior a mother's very den.

I kept thinking of the cubs in the crevice. Their mother might return while we slept. I almost hoped she would.

Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian'south staff writer, has covered narwhals, salmon and the link between birds and horseshoe crabs.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-truth-about-lions-11558237/

0 Response to "Lion Loose Again Other Lion Mane Fallls Out"

Post a Comment